With Spirits of Death, I’m reminded of how pleasing it is to keep discovering new worthwhile Eurocult movies of the vintage variety. Years ago I thought that I might have been coming close to exhausting my selection of every notable Eurohorror / giallo / surreal-art-house-drama film. However, that notion seems to become more and more untrue with time, which is counterintuitive, as it would seem that the more movies of this type you see the closer you would be to seeing them all, but it nonetheless keeps opening up a world that always seems bigger the further you go in.

Spirits of Death is one of those arty, Eurohorror, giallo movies of a particular brand that I can’t believe I went so long without knowing (let’s see if we can coin the term “Sleeping Eurocult” – in winking reference to Agatha Christie’sSleeping Murder). Spirits of Death is directed and cinematographed by Romano Scavolini, who many may know as the director of an infamous Video Nasty from the early ‘80s, Nightmares in a Damaged Brain. He is also the brother of Sauro Scavolini, director of another marvelous “Sleeping Eurocult” Love and Death in the Garden of the Gods.

The film is essentially a gathering of colorful guests, who have been invited by one of the proprietors, Marialé (Ida Galli aka Evelyn Stewart), with mysterious motives, to a spooky old castle. It might sound familiar, and it is, but the gathering turns into a fascinating, candlelit journey into the underground caverns of the castle as well as a delirious entertaining descent into a batshit crazy Fellini-esque masquerade dinner party before things turn over to a more traditional murder mystery, as party guests start getting knocked off by an unseen assailant in the latter half.

Most of the male characters in the film are abusive towards the female characters. The exception is Massimo (Ivan Rassimov) the poet, suggesting that the artist is a more compassionate individual in comparison to the more brutish, philistine individuals with a propensity towards sexual violence and causing humiliation. It’s also interesting that two of the abused female characters, Mercedes (Pilar Velázquez) and Semy (Shawn Robinson), find solace and love by getting away from their racist male chauvinist lovers and into one another’s arms, a possible message about some women being better off leaving their abusive men to pursue lesbian relationships.

While the gothic sights can be somewhat traditional, there is still something much grander about the visuals in Spirits of Death, in comparison to some of its more subtle gothic horror predecessors. The party ultimately shifts to the dark lower levels of the castle, affording an opportunity for the abundance of characters to travel in procession, with multiple characters each holding a candelabra, resulting in a busy but pleasing gothic sight, as the party-goers explore the castle depths.

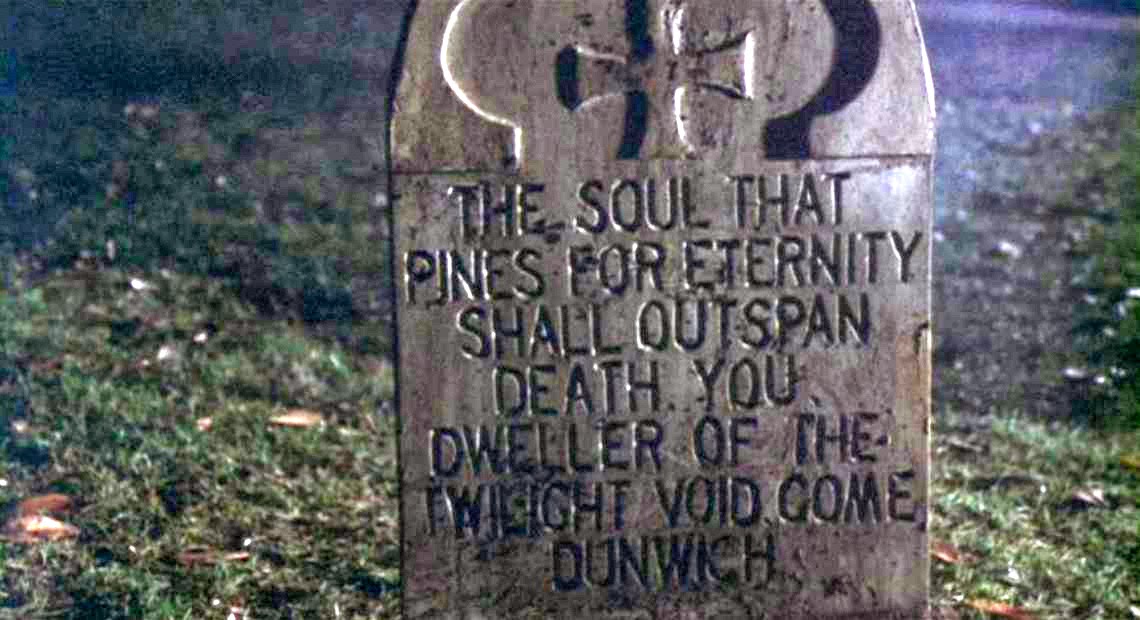

It gets remarkably surreal when an inexplicable indoor storm picks up in the underground crypt-like caverns. The setting starts to become very disorienting, as we start to abandon logic for a more favorable nightmarish experience and the first implication of any spirits of death. With all the screams and emotional outburst for seemingly little reason, it starts to feel a little like a Renato Polsellifilm – think about the tape recorder scene from Delirium. There are several dressed mannequins in the underground area that almost resemble rotting corpses. Eventually, the storm softly subsides from what feels like the result of a few characters relighting the candles, assumedly blown out from the storm, and the film's calming, enchanting theme chiming in. Everyone regains their composure in what feels like some sort of reawakening. The candles are lit and everyone seems in awe at their surroundings now that the storm has passed.

Eventually, the party transitions into a masquerade, as characters borrow different costumes from the corpse-like dummies and undergo bizarre cartoon-like transformations. The movie toys a little with the idea of their being possessed by the spirits of death but ends up feeling more like everyone getting in touch with their wild, primitive sides, a kind of liberalization, becoming informal and hedonistic, acting out behaviors they wouldn’t normally act out. Basically they’re partying, but what peculiar partying it is. It isn’t classy at all but still entertaining to watch. As usual the soundtrack contributes a lot to the crazy dinner party.

The dinner party would have to be the highlight of highlights. It feels climactic despite taking place in the middle of the movie. There's some underlying suspicions that the film might be escalating into a mass sex orgy, but instead, it turns the insanity meter down afterwards and begins to play out as a more low key murder mystery with an immodest body count and, for their time, adequate murder scenes. Also, I never seem to tire of the “oh, it’s you” cliché, establishing that the victims are familiar with their killer.

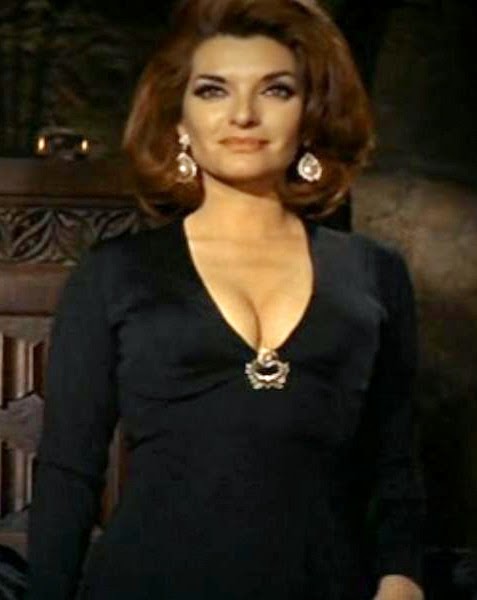

Luigi Pistilli plays a somewhat similar role as his character from Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key, and, as usual, he’s incapable of disappointing. Also, I truly enjoyed Ida Galli as Marialé, appearing almost ghostlike in the background sometimes, overseeing, possibly manipulating, but never really quite participating in most of the events. Aside from Queens of Evil, I always felt she seemed a little underused in everything else I’d seen her in.

Spirits of Death does predict the violent childhood flashback scene that Scavoliniwould explore more graphically in Nightmares in a Damaged Brain. The flashback scene isn’t overused here, used at the very beginning and brought up again at just the right time during the climax to cap the proceedings with a chilling sense of continuity. The climax isn’t that shocking, but I still really like it (especially the way two characters fall dead in each other’s arms). I also couldn’t help thinking a little of the spaghetti western standoff climax.

Upon further re-watches, I found Spirits of Death to be a rather mind-expanding experience. I think it’s a movie that viewers should get a little deeper with and view as art as opposed to simple entertainment; although it’s still very entertaining.

© At the Mansion of Madness

Spirits of Death is one of those arty, Eurohorror, giallo movies of a particular brand that I can’t believe I went so long without knowing (let’s see if we can coin the term “Sleeping Eurocult” – in winking reference to Agatha Christie’sSleeping Murder). Spirits of Death is directed and cinematographed by Romano Scavolini, who many may know as the director of an infamous Video Nasty from the early ‘80s, Nightmares in a Damaged Brain. He is also the brother of Sauro Scavolini, director of another marvelous “Sleeping Eurocult” Love and Death in the Garden of the Gods.

The film is essentially a gathering of colorful guests, who have been invited by one of the proprietors, Marialé (Ida Galli aka Evelyn Stewart), with mysterious motives, to a spooky old castle. It might sound familiar, and it is, but the gathering turns into a fascinating, candlelit journey into the underground caverns of the castle as well as a delirious entertaining descent into a batshit crazy Fellini-esque masquerade dinner party before things turn over to a more traditional murder mystery, as party guests start getting knocked off by an unseen assailant in the latter half.

Most of the male characters in the film are abusive towards the female characters. The exception is Massimo (Ivan Rassimov) the poet, suggesting that the artist is a more compassionate individual in comparison to the more brutish, philistine individuals with a propensity towards sexual violence and causing humiliation. It’s also interesting that two of the abused female characters, Mercedes (Pilar Velázquez) and Semy (Shawn Robinson), find solace and love by getting away from their racist male chauvinist lovers and into one another’s arms, a possible message about some women being better off leaving their abusive men to pursue lesbian relationships.

While the gothic sights can be somewhat traditional, there is still something much grander about the visuals in Spirits of Death, in comparison to some of its more subtle gothic horror predecessors. The party ultimately shifts to the dark lower levels of the castle, affording an opportunity for the abundance of characters to travel in procession, with multiple characters each holding a candelabra, resulting in a busy but pleasing gothic sight, as the party-goers explore the castle depths.

It gets remarkably surreal when an inexplicable indoor storm picks up in the underground crypt-like caverns. The setting starts to become very disorienting, as we start to abandon logic for a more favorable nightmarish experience and the first implication of any spirits of death. With all the screams and emotional outburst for seemingly little reason, it starts to feel a little like a Renato Polsellifilm – think about the tape recorder scene from Delirium. There are several dressed mannequins in the underground area that almost resemble rotting corpses. Eventually, the storm softly subsides from what feels like the result of a few characters relighting the candles, assumedly blown out from the storm, and the film's calming, enchanting theme chiming in. Everyone regains their composure in what feels like some sort of reawakening. The candles are lit and everyone seems in awe at their surroundings now that the storm has passed.

Eventually, the party transitions into a masquerade, as characters borrow different costumes from the corpse-like dummies and undergo bizarre cartoon-like transformations. The movie toys a little with the idea of their being possessed by the spirits of death but ends up feeling more like everyone getting in touch with their wild, primitive sides, a kind of liberalization, becoming informal and hedonistic, acting out behaviors they wouldn’t normally act out. Basically they’re partying, but what peculiar partying it is. It isn’t classy at all but still entertaining to watch. As usual the soundtrack contributes a lot to the crazy dinner party.

The dinner party would have to be the highlight of highlights. It feels climactic despite taking place in the middle of the movie. There's some underlying suspicions that the film might be escalating into a mass sex orgy, but instead, it turns the insanity meter down afterwards and begins to play out as a more low key murder mystery with an immodest body count and, for their time, adequate murder scenes. Also, I never seem to tire of the “oh, it’s you” cliché, establishing that the victims are familiar with their killer.

Luigi Pistilli plays a somewhat similar role as his character from Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key, and, as usual, he’s incapable of disappointing. Also, I truly enjoyed Ida Galli as Marialé, appearing almost ghostlike in the background sometimes, overseeing, possibly manipulating, but never really quite participating in most of the events. Aside from Queens of Evil, I always felt she seemed a little underused in everything else I’d seen her in.

Spirits of Death does predict the violent childhood flashback scene that Scavoliniwould explore more graphically in Nightmares in a Damaged Brain. The flashback scene isn’t overused here, used at the very beginning and brought up again at just the right time during the climax to cap the proceedings with a chilling sense of continuity. The climax isn’t that shocking, but I still really like it (especially the way two characters fall dead in each other’s arms). I also couldn’t help thinking a little of the spaghetti western standoff climax.

Upon further re-watches, I found Spirits of Death to be a rather mind-expanding experience. I think it’s a movie that viewers should get a little deeper with and view as art as opposed to simple entertainment; although it’s still very entertaining.

© At the Mansion of Madness

%2BPNG.png)